TEA, MINIMALISM, AND DIVINE GAZE

Text by: Ming Yuan

Edited by Hassan Khan

an artistic reflection on the similarities in the ethos of tea rituals, minimal art and aesthetics, and multiple religious practices

#minimalart

#aesthetics

#selfoptimisation

#religion

DATE: 01.01.2024

PUBLISHED IN:

TEA BY YUAN Digital Journal

and in

HEISSE LUFT

As groups of snobbish cultural hipsters fussily sip natural wine in major European and North American cities, their Far Eastern counterparts are beginning to pay attention to a traditional non-alcoholic brew, marking the dawn of a new cultural movement devoted to the renaissance of long-forgotten traditional tea rituals. Much like the resurgence of vintage fashions, the reappearance of tea rituals comes with its own funny and ironic contemporary twists.

Though official Chinese history of the second half of the twentieth century has mostly focused on the story of the construction of basic social facilities and the industrial sector, more personal memories of the era often revolve around social transformations, political persecution and the shadow of poverty. On the other hand little attention has been given to the preservation of literature, art, and social customs. Chinese people’s attachment to their antique cultural heritage has therefore slowly been lost, and as interest in traditional skills and knowledge diminished the holders of these skills and inheritors of this knowledge were forced to change their careers.

Now however, after years of economic boom in China, large segments of the population have gained the freedom to spend their newly found wealth on consumer goods as well as leisure activities. As life gradually becomes more comfortable, people have more leisure time and therefore the desire to be entertained; they begin to read more books, watch deeper films, and discuss culture more intensely. As more attention is given to the culture sector, a weakness in national cultural identity is slowly becoming more clear. The middle-class intelligentsia has, as usual, bore the brunt of expressing their dissatisfaction with this situation. Following their critiques, a collective desire to bridge the cultural gap between the traditional and the contemporary seems to grow stronger every day. Therefore a lot of public funding and private investment has turned towards rediscovering and rejuvenating ancient traditions like the traditional tea ceremony.

Due to the disappearance of people with knowledge of these traditions a movement to collect information from historical objects has begun. However, the information revealed through old paintings, literature and even excavated archaeological objects is not really enough to fully reconstruct a functioning precise system. The true historical tradition of the Chinese tea ritual is actually till today still an enigma.

The lack of material evidence and historical information has not dampened people’s enthusiasm. The savvy entrepreneurial spirit of the Chinese merchant has, once again, found a way to overcome this frustrating impasse. The disadvantage of a lack of information has been transformed into the advantage of everything-goes interpretations. Numerous new cultural activities have emerged, inviting exploration and immersion into the lifestyle of ancient Chinese folk. We are talking about binge-watching costume dramas, Han dynasty cosplay, DIY-ing makeup with ancient recipes, and of course, hosting and attending tea ceremonies.

Soon different invented schools of tea ceremony with their own rules, aesthetics and groups of aficionados appeared. There are tea parties mimicking the ascetic style of ancient monks, others recreating the flamboyant style of palace aristocrats, and some guided solely by personal inclinations. Different schools of tea brewing have emerged from this pool of limited knowledge and have been filling out the missing pieces of what we know with their own self made decisions. Presently, the most popular school is Gongfucha.

The freedom to interpret extends beyond brewing methods; it's shaping an invented past, subtly transforming ideologies and aesthetics. Within that short simple word ‘tea’ is a complex cultural ecosystem. When the partakers of these new rituals drink ‘tea’ they are not only enthusiastically imbibing a roasted leaf infused soup, a lot more is going down: values, theosophical ideals and lifestyle presumptions all revolving around the act of modernizing traditional aesthetics to fit a twenty-first century lifestyle are all being imbibed as well.

Though historically, the tea ceremony belonged to aristocratic circles, the tumultuous changes and rapid modernization over the past century has democratized this privilege encouraging much broader participation. The tea ceremony has now become the domain of the new Chinese bourgeoisie. One can have a great tea ceremony not only in an exquisite teahouse in Shanghai, but also on the street of a peaceful neighborhood in Chaozhou. Both affordable and lavish tea-ware can be easily purchased on the omnipresent Taobao website.

In the realm of aesthetics, a diverse spectrum has emerged in this new tea culture, ranging from minimalistic to highly decorative designs. However we can safely claim that the majority of tea drinkers seem to gravitate toward a rather minimalist ideology of tea drinking. In tea rituals, we often see things arranged in a pleasing geometric order, almost resembling a minimalist artwork where form, shape, material, color, and production processes are reduced to the bare minimum. Mid-Century American Minimalist artists, such as Richard Serra, Donald Judd, Frank Stella, Carl Andre, Robert Morris and Tony Smith who intended to strip off all ornamentation and aim to produce art that represents nothing more than what it truly is—no fluff, no extras, come to mind.

Some artists do not stop at the physical dimension of this reduction, they wish to produce art with a visual language that has no personal feelings creeping in, however these minimalist artists are meticulous in framing their art. They do not tolerate the romantic approach of communication, but rather try to express their ideas through associations, through the manipulation of the medium, the title, and of course the discourse. Symbols might be interpreted by the viewer subjectively, but facts remains objective and precise. The use of facts, not symbols, shows the artist’s pursuit of radical honesty. The minimalists’ way of presenting themselves and their artworks without fabulation is strangely similar to the philosophy of contemporary tea drinkers.

The creation of an artwork’s aura is indispensable to both the minimal artist and the tea host. Walter Benjamin defines the aura of an artwork as its unique presence in time and space understood through its cultural context. One way artists produce aura around their works is through the creation of extensive texts. Their texts dictate the terms in which their works are to be received, and locates them in the most opportune position relative to the dominant critical discourse. The minimalist artists' eagerness for success maybe displays a somewhat impatient itch for opportunity. This stands as a significant difference in mentality between them and participants of the tea ritual. Tea drinkers are in no rush to succeed!

Instead of manipulating the form and context of the artwork, the tea ceremony host manipulates the utensils, location, clothes, as well as bodily movements, and conversation. In Ch'a Ching, the Chinese tea god Lu Yu (BC 733-804) who set through text and illustrations the definitive description of Tang Dynasty tea utensils, elaborated the art of manipulation of tea utensils to create an aura for the tea ceremony. The setting and location of the tea ceremony also play very important roles in the production of aura.

Similar to stringent puritan Christian dogma, the aesthetic and ethics of tea rituals can also be executed in strictly disciplined austerity. Sen no Rikyū(1522-1591), the most praised Japanese tea master till this day, practiced the minimalist ethos in every detail of his ceremonies, no matter the status of his guests. Under the intoxicated lush lifestyle of the Japanese aristocrats, his ascetic aesthetic pursuit made him an extremely desirable spiritual leader amongst both civilians and royalty. Paradoxically it seems the more lavish one's life becomes, the greater the yearning for a return to simplicity and liberation. For them simplicity represents ultimate luxury. Rikyu’s design of his ceremonies is guided by his pursuit of purity, of clearance of dross, and of ultimately revealing his true self. His popularity eventually irritated the conceited Imperial Regent Hideyoshi who forced Rikyu to commit seppuku.

When I initially introduced the revived tradition of the tea ceremony to my European artist community, I quickly found out that tea didn’t resonate as much with the art crowd as yoga did. So, my astute business acumen led me to switch my home base to the spiritual industry. I began incorporating Chinese tea rituals into yoga classes and spiritual meditations, successfully merging both practices. The yogis comprehend the philosophy and the idea of tea drinking naturally, and it is easier for them to truly appreciate the sensual as well as spiritual aspirations of the ritual.

It is no surprise that the revival of traditional activities like the tea ceremony comes at a time where the feverish obsession with personal fitness is becoming widespread amongst many young people for whom sports and physical health have in some ways replaced the role of art and literature. Not only is dopamine secreted when doing sports, but also when watching others do sports. As spectators, the global masses are much more passionate about watching football games than going to a museum. The ancient ethos of excelling through physical competition like in the Ancient Greeks’ Olympic Games has been replaced by passive spectatorship. It is therefore not surprising that pursuing excellence in sports has been transferred to other forms of self-improving activities such as personal training, yoga, and the various casual sports activities of the contemporary world.

In yoga and meditation as well as physical workout, one does not compete with others but with one’s own self. In the tea ritual, one focuses solely on movements, thriving for absolute control over body and mind. Brewing tea is a competition with one’s self and requires a peaceful, focused state of mind. The brewer use this attention to navigate through interactions with the numerous complicated utensils. While physical training in solitude is one of the few socially acceptable times to be lonely. It is also the only socially accepted form of pure narcissism. The period of training and waiting for recognition and success offers the most intense forms of vanity and self-absorption. The training of one’s body requires isolation. So does the training of the spirit. Puritan ascetics devotedly adhere to specific rules aimed at refining their souls, believing that by presenting these refined souls as offerings to God, they could gain entry to an eternal, blissful heaven. They isolate themselves and train their whole lives in remote locations and they only exit this kind of training when they die. In secular life, our casual lifestyle training also requires temporary isolation from society. But our exit from solitude does not need to wait until death. We exit our solitude when we walk out of the gym. Our exit is our re-entry into society’s gaze and judgement.

For a tea brewer, preparing tea is akin to practicing meditation in solitude. The act of drinking the brew signals the brewer’s return to the ritual. Looking, smelling, sipping, and swallowing compose a series of movements that go beyond the functional; these are not just a sequence of actions to quench thirst, they are a metaphor. In a similar way to the Christian eucharist, it manifests our aspirations to improve ourselves by disciplining our bodies and minds, and ultimately to emerge as our truest selves. In Christian ritual the re-enactment of the last supper brings the believers closer to god’s virtues. It rewards them for their devotion to the faith and encourages them to vow to continue to devoutly uphold the creed. In tea rituals, the first sip of tea rewards the brewer for their patient practice and spurs on further acts of self-optimization.

Some religious communities who also wear uniforms (Catholic and Buddhist monks, ultra-orthodox Jews, Amish, etc) reject change of historical aesthetic fashions, because they understand themselves as trans-historical and trans-temporal; their beliefs and ways of life as eternal and immortal. They claim to strive to live a simple and unornamented honest life in preparation for the judgement of God. Such visions seem to also inhabit avant-garde designers, minimalists, and contemporary revivalist tea drinkers. Uniforms demonstrate that an individual is committed to trans-temporal values. In the tea ritual, both the humble garments and the utensils serve as uniforms.

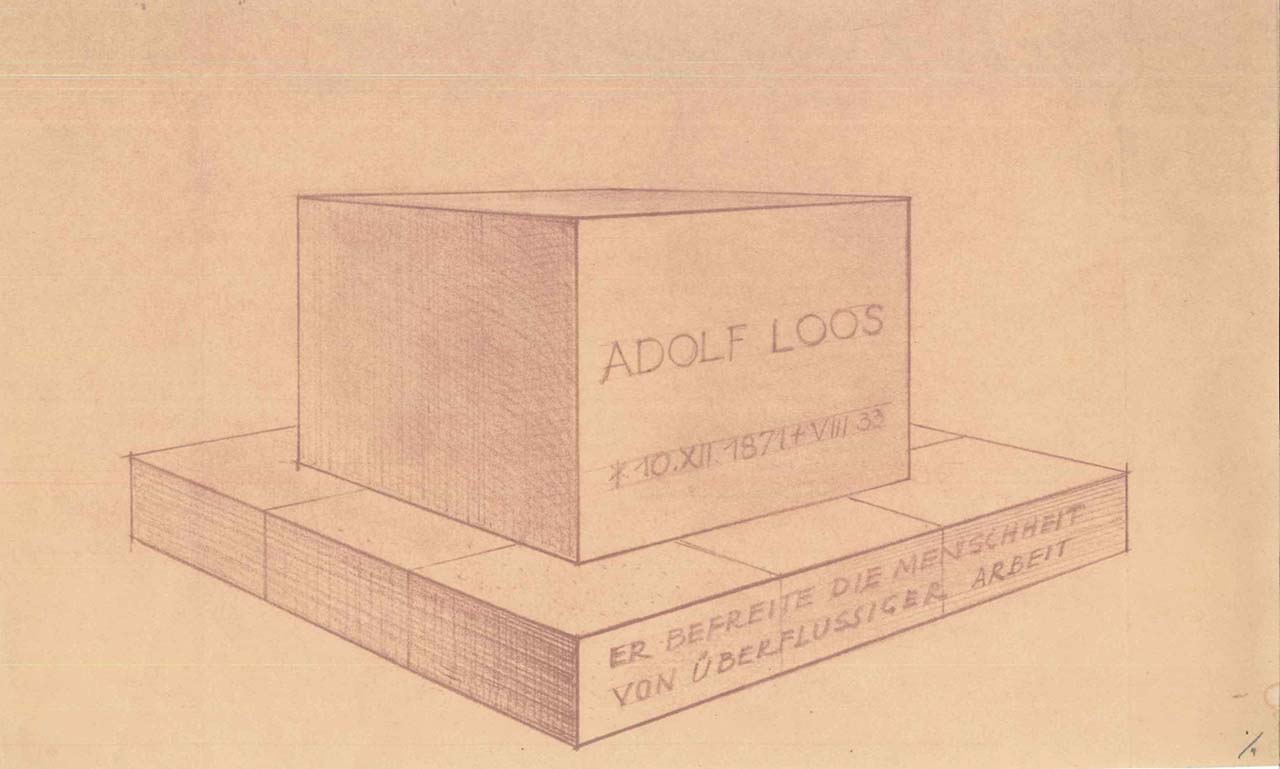

Adolf Loos in his essay Ornaments and Crime condemns decoration as a sign of depravity and vice and design then takes on an explicitly ethical dimension. The argument goes that decoration deceives the viewer, and distracts them from the ethical aspect of the design which is the honesty of the craftsman. That honesty can be seen in the refinement of the artisan’s skills and in the quality of the material. For Loos, the modern human is expected to present him or her-self to the gaze of others through honest, plain, unornamented, ‘under-designed’ objects that reflect them. In a way, the unornamental minimalist object democratizes the divine gaze of God on Judgement Day. With these designed objects around us, we show our supposed honest true self not to god, but to spectators around us.

The cultural fault zones of the twentieth century have inspired China's petit bourgeois intelligentsia to revitalize antique traditions. The lack of historical information has naturally pushed people to shift their attention from material evidence to intangible cultural heritage. In this accidental collision, the collective will of society has synthesized made-up traditions and avant-garde aesthetics into a new ideology.

Fueling the modern craze for sports and meditation is a religious devotion to self-improvement, which is no longer understood through divine salvation. Specific teachings of various religions and sects have been hybridized into a transtemporal, transhistorical, and transcultural set of self-requirements that have become elevated into an ethical dimension. Where religion once was, design has emerged,ethics become aesthetics and form. The central idea of a certain type of puritanical modernism of abandoning the aesthetics of decoration and paying more attention to the ethics of "design" concepts has been sublimated into a form of value accumulation which was facilitated through the massive class and social transformations of the late twentieth century. Examples are many: In Europe, yoga and meditation movements have been hugely popular since the sixties; In North America it manifests in artists' pursuit of minimalist art and in contemporary China a new petit bourgeois is obsessed with trying to reproduce a made up traditional tea ceremony.

Tea cup with minimal aesthetics

installation view of Carl Andre

installation view by Carl Andre

The Classics of Tea, Lu Yu

Death of tea master, 1989

A movie about Sen no Rikyu

A movie about Sen no Rikyu

Tomb Idea of Afold Loos